Georgia O’Keeffe: Her Romanticism of Nature

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) was a modernist painter keenly attuned to the natural world. Myself and Lauren Henry held an exploration of her collected works through a guided art workshop on colour theory, observational sketching and dimensionality at the beautiful Moseley Gifts and Gardens.

Below is a summary of the immersive seminar and discussion I led on her life and significance. Multiple chairs and tables were set up around the centre, the vibes were immaculate and we all left with a greater appreciation of community, flowers and how to make an artistic home for yourself, within yourself.

Georgia O’Keeffe was one of the most significant painters and icons of modern American art and she was born in 1887. Her work is endlessly surprising and devoted to discipline, subtlety, tonal gradation, composition, dreamlike colour fields and the minute finer details of nature.

Her work blurs the boundary between the photographer’s zoom and abstraction. She was wholly devoted in an almost eremitic way to nature. Her paintings, though vibrant, are not harsh - the textures are soft. The landscapes she lived in are presented alongside skulls or aridity that may be unfamiliar, but they are not discomforting to gaze into; especially when compared to other avant-garde modernists of the 1920s coming from Europe.

She managed to place ordinary natural objects in the centre of their own context, isolated from how most painters frame or associate flowers, skulls, bones, leaves, buds and stamen or even the sky. She could let the smallest things fill an entire plane with only ambiguous gestures towards their beginning and their end.

She was misunderstood and mis-marketed by one of the greatest loves of her life, yet throughout her career her possession of nature and the objects she loved did not fail her. Creating a non-verbal language to engage with nature freed her understanding of herself.

Her unique balance of light, form, colour and composition often meant people assumed her work centred on sensuality, or feminine sexuality. This implication and the sublime sits under the surface of many paintings such as Grey Line with Black, Blue and Yellow, 1923.

Grey Line with Black, Blue and Yellow in 1923 currently on display at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston© Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Her paintings of plants and flowers are not just stiff botanical specimen drawings — they have huge visual impact because the subjects are so zoomed into frame that the typical structure of a petal becomes ambiguous, the plane composition elongates the interior and there’s a tension between what our mind wants to visualise and what’s there.

In a lot of her work, because it is often just one or two flowers in a frame, there’s an implication that we’ve been drawn in , head down, nose to the petal, to look at the detail she sees, and at such an intimate level your mind’s eye ‘fills in’ the rest of the larger flower. The tension of being so close implies that we’re gazing at a moving and undulating world below the surface or within the centre of something. And in the time we take to look at each painting for something we recognise, we’re already decoding how she already felt about the subject.

In paintings like in Red Canna, 1924 the repeated curves of the petals creates a sense of movement within the flower (rather than the same sense of movement you’d see in a portrait of people mid-pose), an animated energy flows as our eyes moving over each fold, each delicate edge — the canna blooming in front of us because there’s so much dimensionality and light coming from within the flower, like a solar flare.

Red Canna 1924 is part of a series starting in 1915 © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In her even more abstract work the plant forms, petals, leaves, stems, stamen ect… and the direction we’re zooming into, which section of nature is being framed become even more ambiguous and it's our implicit associations…that curves mean this, red means that, creases could be this … within recognisable designs that forces what we see. Such as Music Pink and Blue II, 1918. Sure this could be the interior lips, but also the opening of an eternal cave, the vibrations of a ripple in water.

Music, Pink and Blue No II 1918 currently on display at the Whitney Museum of American Art © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

These paintings I think quite brilliantly communicate the ambiguity of true abstraction, because there is so much unknown, so many unending harmonic and complimentary layers within the curved figure we are presented with. This painting is named after music of which she said, “Singing has always seemed to me the most perfect means of expression. It is so spontaneous. And after singing, I think the violin. Since I cannot sing, I paint.”

Growing up in Wisconsin she learned to draw and paint as a child. After graduating high school she developed her craft in art training at School of the Art Institute of Chicago and then at the Art Students League of New York. Under William Merritt Chase she studied technique, perspective, shading, charcoal, oils, watercolour, and brushstroke. One of her other early teachers was Arthur Wesley Dow, who informed her central artist’s philosophy which was to fill the canvas in a beautiful way. Dow was not focused on good art being an exercise in creating exact replicas of objects but that art should too capture feeling about the object. He also integrated Japanese art into the curriculum for its formal qualities of composition, the imbalance or power of spatial relations, and colour theory. He taught her to focus less on the objects themselves and more on the relationship amongst them or between the artist and her subject. He advocated for asymmetry and the balance of light and dark while also emphasising flatness and the decorative aesthetics of Japanese prints.

This sensibility came up in her work later on in life an its more useful to think of her work not in periods but with motif repetitions, as she developed new scales and ways of repeating the same asymmetries, strokes, subjects and compositions over and over again, over the course of her very long career.

For example, from 1916 to 1962 she maintained using asymmetrical blue lines following the similar principles that she had been taught, compelling the viewer to focus on the power and beauty of negative space. “It is lines and colour put together so that they say something. For me that is the very basis of painting. The abstracted is often the most definite form for the intangible thing in myself that I can only clarify in paint.”

The blue calligraphy form in 1962 has so little on the canvas but expresses the deep kinship and emotional connection she felt to the landscape, specifically the Chama River by Ghost Ranch. As she began to understand a subject (flowers, rivers, clouds or otherwise) better her work would become more abstract as she learned to view the natural world for herself in her own language. It could be said that her early charcoal compositions of plant-like, nature-adjacent patterns picked apart specific aesthetic qualities in flowers —bulbous buds, curled stamen, repeated coils — to express the delicateness of how she was feeling as a young painter. As O’Keeffe said, “I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn't say any other way - things I had no words for. I had to create an equivalent for what I felt about what I was looking at - not copy it.”

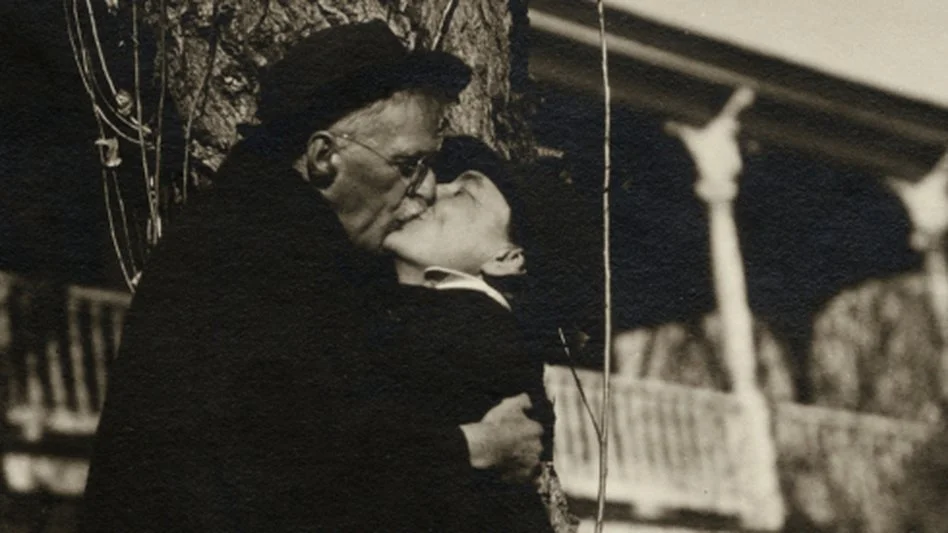

In the autumn of 1915 she sent some of her charcoals to a friend in New York, who showed them to a prominent photographer and art dealer, Alfred Stieglitz. Impressed by her works, they met in 1916 and Stieglitz held an exhibition of her work in his 291 Gallery.

His gallery at 291 Fifth Avenue was one of those now-hallowed New York spaces where modernism took root in the American art scene. She worked as an illustrator for a little while but she was unable to continue her studies due to financial difficulties. So she moved to Texas to teach. She loved Texas and the landscape and her life and dressing outside of the gender norms of the time and her friends and suitors and driving into the desert to chase the tails of a storm . “Why of course I feel free, it never occurred for me to feel any other way.”

She had other lovers but continued a correspondence with Alfred Steiglitz. In their lives they sent over 25000 letters, sometimes 2 or 3 a day and some of them 40 pages long (O’Keeffe deposited a large number of them to archivists on the condition that they remain sealed until 20 years after her death). Her love life weaved into her work and influenced her career massively. Her letters as an emerging and thoughtful woman artist, detail the peak of a 20th century situationship with an avoidant older gentleman. When she got covid-19 ala the Influenza of 1918, she was thinking of finally moving back to New York, more convinced of her work and herself everyday since the first exhibit back in 1916. Steiglitz replied: "What do I want from you? — ... Sometimes I feel I'm going stark mad — That I ought to say — Dearest — You are so much to me that you must not come near me — Coming may bring you darkness instead of light — And it's in Everlasting light that you should live." and “ "All I want is to preserve that wonderful something which so purely exists between us."

But eventually he arranged for her to leave Texas and come to New York.

He stayed married and represented her as her art-dealer-manager, and they wrote letters and fell deeper in love. In that time she produced Flower of Life, which is one of my favourite O’Keeffe pieces. He presented her work alongside exhibitions of nude photographs he’d taken of her, beginning the forever misconception and association of her work with her sexuality. Eventually after he divorced Emmeline Obermayer, Georgia and Alfred were married in 1924.

By the late 1920s Alfred had began another affair with another new woman, a new muse loomed on the walls of 291 Fifth Avenue and Georgia made her first visit to New Mexico (accompanied with Rebecca Strand who had first brought her from Texas to New York). She found a place of creative solitude so remote that it was designated only by skull.

She erased the conventions of marriage, femininity (she got a driving license and hung out with ranch hands on epic camping trips) and tried to erase herself from the public eye in order to know herself, “There is so much life in me and makes me feel I am growing very tall and straight inside and very still. Maybe you will not love me for it but for me it seems the best thing I can do for you. I hope this letter carries no hurt for you, it is the last thing in the world I want to do.”

Alfred replies, “I am broken.”

As is often the case in love we cannot escape the meaning and significance that those who enter our lives have. Sometimes, especially for creatives, romance is not allowed to conclude into ‘right person, wrong time’, ‘wrong person, right time’, but instead ‘my experience of this person and their perspective will forever define this time’. It is the work of memory, creative imagination and language to unravel that perspective, non-verbally O’Keeffe was impacted by Steiglitz’s love of photography, who made her one of the first brands in American art, and he also exposed her to the new medium at the time, which went on to inform her work. Her paintings radically look at nature from this abstract perspective perhaps because of the early experiments in close-up photography of Paul Strand, who was part of the Stieglitz circle and a close friend of hers too.

My favourite examples of this experimentation with scale and perspective is the Pelvis Series 1947- created 2 years after Stieglitz passed away and Georgia had permanently moved to New Mexico, each painting looking through something that was once alive, alas the desert shows no kindness. The piece below, in isolation from the rest in the series, without knowing how she built towards a simple blue sky isolated in bone, is so beautiful and alien, like an inverted egg, like she’d cut a piece of the sky out and placed the fresh orb of it on paper.

I love this piece most because it’s almost like an eye is staring back at human bones, the ever present sky making the viewer subject.

Pelvis Series 1947 © Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

“When I started painting the pelvis bones I was most interested in the holes in the bones—what I saw through them.”

She loved New Mexico because of the rich colour palettes of the plains. The form and colour of landscapes at least did not have the sexual implications of her previous subjects, rivers and bones were not gendered the same way as flowers, even as she repeated curved motifs and continued with bold provocative uses of colour.

She also loved New Mexico because she made it a home for herself to satisfy the terms of her own curiosity and ambition, beyond the will of heartbreak, beyond the assumptions of the man doing the breaking. Looking at photos of Georgia’s homes and her paintings of her favourite door I think of the Sandra Cisneros poem, A House of My Own.

When asked by Andy Warhol towards the end of her life if she’d consider wearing contacts to change her appearance she replied, ‘“I’ve lived up there at the end of the world by myself for a long time. You can walk around with your thing out in a field and nobody cares. It’s nice.”